We at New Zealand Birds would like to acknowlege a group of the people who have made outstanding contributions to the environment, here in NZ and around the world. You will find their contribution both amazing and inspiring. They, every single one of them, are wonderful.

How did an American women come to play a large part in the ongoing efforts to save the kakapo? This was a question the New Zealand member of parliament, Matiu Rata, asked Rebecca Dennett when he met her in 1991.

“I met Matiu Rata the first morning in New Zealand. The plane landed about 6:30 am, and I went to the Alpine Hotel in Auckland. I took some of my luggage up to my room, and when I came down to get the rest, Matiu was there talking to the girl at the desk. She was telling him about the American woman who was there because of the kakapo. He was intrigued and wanted to get to know me. He took me to the War Memorial Museum (I think that was the name) and showed me the display of stuffed kakapos”.

In 1984, Rebecca saw a documentary called ‘Birds of Paradox’. At the end it showed Alice and Snark and a male booming. She was intrigued as she thought they were extinct and started trying to find more information about them. “The more I found the more I wanted to know. Somehow, this most wonderful of all birds struck a chord in my heart and soul, and I never got over it. I decided I couldn’t bear it if they should become extinct.”

Rebecca had a contact who knew Don Merton, the man who had been at the forefront of efforts to save the Kakapo since the 1960s. She began corresponding with those in the New Zealand Wildlife Service involved in saving the kakapo, noteably Ralph Powlesland, who was working on Kakapo at Little Barrier Island at that time.

Rebecca eventually saved enough money to go to NZ in January ‘91, and served as a kakapo volunteer on Little Barrier Island with Ralph Powlesland. “I had never been out of the country, so this was quite the adventure for me. I was terrified, but determined. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to see a kakapo although one did come down to the bunkhouse but Ralph didn’t wake me up. It was Richard Henry. They had thought he was dead and they were very pleased to find that he wasn’t. They said a kakapo hadn’t come down there in years. I’ve always felt that he came to see me, but it just didn’t happen. I guess I won’t get to see one until I die. I believe all animals have souls like us.”

Rebecca, however, was there when they found a couple of nests and 2 chicks which survived that year. It was the first time chicks had survived since they had found Snark. “I got to ride in the helicopter with the incubator and kakapo eggs between my feet to hold it steady. We landed at the Auckland Zoo and the news crew was there. We were on the news that night. Unfortunately, those eggs didn’t survive. It was a great disappointment. I’ll always treasure my time there and I wish I could go back.”

On her return to the States Rebecca launched “Kakapo Rescue” to raise funds in USA for kakapo conservation efforts in New Zealand. “Rebecca subsequently sent me several cheques for US$5,000 which were a huge help in our very expensive field program,” says Don Merton who was made honorary president of Kakapo Rescue.

In 1993 Rebecca arranged for Don Merton to attend and deliver a paper on kakapo at the American Federation of Aviculture’s National Convention in Salt Lake City — hosted by the Avicultural Society of Utah. “This was a highlight of my life — meeting Rebecca, being greeted at airport by a genuine New Zealand Maori group who performed a traditional welcome, and a little girl — Jody Anderson — dressed up in a kakapo costume! Also, in meeting some of the world’s leading aviculturists, bird vets, diet specialists, I learned a great deal and clearly my attendance at the Convention benefitted the kakapo program.”

Afterwards, Rebecca took Don Merton to see the Grand Canyon and Zion National Park with which Rebecca’s family has had a long association.

Rosalie Barrow Edge was born November 3, 1877, to a family of wealth and position in New York City. Her father was a cousin of Charles Dickens ...

He serves his country best who loves the land itself.’ So wrote Charles Fleming in the winter of 1972 in a poem he called Environmental Patriot. This was a time when the battle to save Lake Manapouri had not yet been won and conservationists were girding their loins for future fights for native forests.

He serves his country best

Who loves the land itself.

Not just the people sitting fat

And bland, sinking beers midst natural resources

They have messed.

Not just the shrunken babies dying

In the tired exploited dust

Derived down–degraded soil–eroded empires.

Not just the business men, developers

Of housing projects, purveyors of plastic cups, the just

Lawyers who emphasize

The equity of private enterprise.

Not the philosophers who insist

That human values far exceed non–human things

(Especially when pissed),

And scoff at those who see beyond

The work of men to Thoreau’s bond.

They coarsely jest

At him who loves the land itself

And serves his country best.

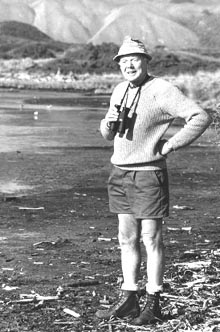

After a long and distinguished career as scientist, Sir Charles Fleming became a leader of the conservation movement in New Zealand as a result of a passionate guest editorial in the Listerner in 1969 entitled ‘Mammon on the Mamaku’.

"State forests of the Mamaku Plateau, flanking the highway to Rotorua from the north, have produced rimu and other timber over the years but have remained the most accessible place in the North Island to see native birds — robin, tit, rifleman, ... parakeet, kaka — and the rare kokako if one is lucky. Now, screened from the highway by a pathetic hedge of tawa bush — too narrow for permanence and inadequate as bird habitat — 37,000 acres of native forest are destined for conversion. In preparing the ground for pine planting, native growth must be completely removed by defoliant spray, chainsaw, bulldozer and fire. In the process thousands of native birds will die unseen as surely as if shot ..."

‘Mammon on the Mamaku’ established Charles Fleming as a leader of the conservation movement of the seventies and eighties, through which he fought, first for the Mamakus, and at the same time for Lake Manapouri and then for many of this country’s remaining lowland native forests and other ecosystems.

The 1984–elected Labour Government had held the Environmental Forum in March 1985 at which the conservation movement pressed the government to ‘bring the green dots together’ as they called it, into a new government department, a nature conservancy or Conservation Department. At the forum Charles gave perhaps his most impassioned speech.

A few days before the forum someone in the Forest Service had used a bulldozer to clearfell a stand of Hall’s totara in Waituhi, southern Pureora, in what looked like a final act of vandalism to spite the conservationists. Charles began his speech:

“Mr Chairman, last night ... Television New Zealand documented the Waituhi Fiasco... through the recent clear felling [at] Pureora Forest Park, of virgin ... Hall’s Totara. As a result, the whole of New Zealand, it seems to me, will understand why the conservation groups will not have confidence in leaving native forests and other natural areas ranked as worthy of preservation in the hands of ‘developer departments’.

Sixteen years ago I wrote an editorial in the New Zealand Listener, under the title ‘Mammon on the Mamaku’, deploring the leasing of the Mamaku Forests to NZ Forest Products Ltd. for conversion to pine, without public input into the decision ...

One of the great apostles of the conservation movement, an American forester named Aldo Leopold, wrote in his book A Sand–Country Almanac: ‘Wilderness is the raw material out of which man has hammered the artefact called civilization. Wilderness was never a homogeneous raw material. It was very diverse, and the resulting artefacts are very diverse. These differences in the end–product are known as cultures’ ...

In Maori tradition, the Kokako, (which suffered badly from Mamaku conversion) gained its long legs for leaping through the branches as a reward for bringing refreshment to Maui Potiki, exhausted after his struggle with the sun. To biogeographers, the Kokako is a result of adaptive radiation, an evolutionary process, in New Zealand’s long–continued isolation. Its weak flight and strong legs reflect the absence of predators.

If we have faith in the progress of education, our mokopuna, and their mokopuna in turn, will rejoice to visit New Zealand wilderness — as they are doing in increasing numbers — for understanding and recreation.

Charles ended his speech with a plea: New Zealanders have no confidence in the record or the promises of the ‘developer departments‘. Please let us have a Nature Conservancy, holding these lands we rank as precious for all New Zealanders. If you do, this ‘green dot’ can die happy”.

Sir Charles died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 71, happy in the knowledge that the green dots had come together in the formation of the Department of Conservation.

Reference: Charles Fleming, Environmnetal Patriot, a biography by Mary McEwen, Craig Potton Publishing, 2005.

Herbert Guthrie-Smith, (1862-1940). New Zealand farmer and conservationist. His strong conservation ethic evolved from direct experience as a run-holder and observer in the field. His books, especially Tutira: the story of a NZ sheep station, graphically document the impacts of human activity on New Zealand’s unique environment.

Reference and more information: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

“I will leave a sum in my last will for my body to be carried to Brazil and to these forests. It will be laid out in a manner secure against the possums and the vultures just as we make our chickens secure; and this great Coprophanaeus beetle will bury me. They will enter, will bury, will live on my flesh; and in the shape of their children and mine, I will escape death. No worm for me nor sordid fly, I will buzz in the dusk like a huge bumble bee. I will be many, buzz even as a swarm of motorbikes, be borne, body by flying body out into the Brazilian wilderness beneath the stars, lofted under those beautiful and un–fused elytra which we will all hold over our backs. So finally I too will shine like a violet ground beetle under a stone.”

More information: In Memory of Bill Hamilton

Richard Henry, who has been called the "hermit of Dusky Sound", is probably New Zealand's first true conservationist. He is known mainly for his valiant efforts to move Kakapo to a safe haven on Resolution Island. However, his greatest contribution was in his discriptions of the Kakapo, their breeding and feeding habits, which were used to some benefit by wild life experts in later efforts to save these birds.

Reference and more information: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) is considered the father of wildlife ecology and a true Wisconsin hero. He was a renowned scientist and scholar, exceptional teacher, philosopher, and gifted writer. It is for his book, A Sand County Almanac, that Leopold is best known by millions of people around the globe. The Almanac, often acclaimed as the century’s literary landmark in conservation, melds exceptional poetic prose with keen observations of the natural world. The Almanac reflects an evolution of a lifetime of love, observation, and thought. It led to a philosophy that has guided many to discovering what it means to live in harmony with the land and with one another.

"He is to science what Gandhi was to politics. And his central notion, that the planet behaves as a living organism, is as radical, profound, and far-reaching in its impact as any of Gandhi's ideas." New Scientist

"If we see the world as a superorganism of which we are a part - not the owner, nor the tenant, not even a passenger - we could have a long time ahead of us and our species might survive for its "alloted span". It all depends on you and me."

Photo Comby Institute:

More information:Biography

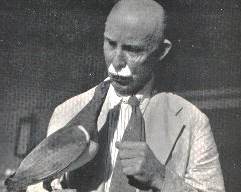

W. R. B. Oliver, 1883-1957, is probably best known for his works on birds - particularly his major book, New Zealand Birds (1930, with a major revision in 1955) which is still among the most valuable sources on our birds.

However, his interests and accomplishments were varied; his revision of T. F. Cheeseman’s Manual of the New Zealand flora , published in 1925, and his monographs of such plant genera as Metrosideros, Dracophyllum, Coprosma, Coriaria and Aciphylla earned him worldwide recognition as a botanist. His monograph on the moa (1949) and his paper on bird evolution (1945) as well as his book on New Zealand Birds - gave him equal status as an ornithologist. His account of the whales and dolphins of New Zealand (1922) remained the standard work on this group for many years. He retained his early interest in molluscs and published several useful revisions. Another early interest was inter-tidal ecology, and his 1923 paper on marine littoral plant and animal communities was a pioneer work of international standing.

Reference: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

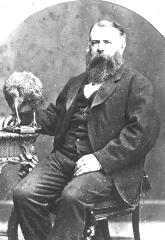

Thomas Henry Potts, 1824-1888, is best known for his contribution to Walter Lawry Buller’s Birds of New Zealand.

Through his father Potts inherited both a fortune and the family firm of Branders and Potts, later one of a group which formed the Birmingham Small Arms Co and it was this fortune which allowed him to indulge his passion for natural history.

After the death of his parents, Potts emigrated to New Zealand where his father-in-law had settled at Rockwood in the Malvern Hills, Canterbury. In 1858 the family lived at “Ohinetahi”, Governors Bay, Lyttelton Harbour, the home most associated with them; and from here Potts made extensive explorations into the mountainous districts of Canterbury, Westland, and Banks Peninsula.

Pott’s acute observations of nature gave to New Zealand literature unique records of birds and flora even then retreating before the progress of European occupation. Among new species discovered by Potts were the Roa or great grey kiwi, and the black-billed gull.

Potts was a member of the Canterbury Provincial Council, for Port Victoria, from 1858 to 1861 and from 1866 to 1875, member of the House of Representatives for Mount Herbert from 1866 to 1870, and was the first parliamentarian to advocate forest conservation.

Best remembered for “Out in the Open”, a collection of scraps of natural history, Potts was a contributor to the Canterbury Times, the Field, London, the New Zealand Country Journal, the Journal of the Linnaean Society, the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute.

Reference: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

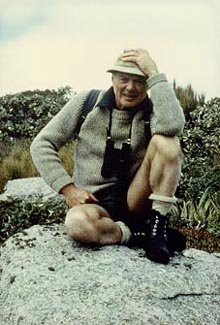

Dr L.E. Richdale, 1900-1983. Dr Richdale is probably best known for his efforts to protect the royal albatross colony at Taiaroa Head near Dunedin at a time when public support for the principles of conservation was limited. He spent long hours guarding albatross nests at Taiaroa Head in order to protect the eggs. The Otago branch of the Royal Society of New Zealand was eventually able to establish a sanctuary for the birds, and the Richdale Observatory at Taiaroa Head was opened in 1983.

Dr Richdale spent the largest part of his life and is remembered by thousands of Otago city and rural students and their teachers as ‘Mr Rich’ the ‘Nature Study Man’. His main interest had been in alpine flora, but in 1936 he was introduced to the study of birds - initially the yellow-eyed penguin and the royal albatross.

Over the next 30 years, in spite of a teaching job, he undertook field research in many remote locations. This resulted in over 105 scientific books, papers and popular articles on a wide range of birds, mainly seabirds. His work on the sexual behaviour of penguins became his most famous work and earned him a international reputation.

A Fulbright fellowship awarded in 1950 enabled him to study at Cornell University, New York state. On his return he received a Nuffield Foundation grant for work on animal ecology and population studies. He was an honorary lecturer at the University of Otago from 1940 to 1952, and received a DSc in 1952 and the Hector Memorial Medal and Prize of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1953. He was a fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand, fellow of the Linnean Society of London, and a founding member of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand. In 1982 he was appointed an OBE for services to ornithology.

Reference: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

For over 30 years, John Wamsley has been striving to save Australia’s indigenous wildlife.